Are You Less Safe in an Uber?

By Robert McGarvey

Blunt question: do you feel less safe in an Uber or Lyft than you do in a properly medallioned taxi driven by a properly licensed taxi driver? The National Limousine Association is betting that you do – at least that you will after seeing its fear provoking TV ads.

The pitch is that ride sharing drivers haven’t been drug tested or thoroughly background checked.

But licensed taxi drivers are both, said the National Limousine Association.

Ask the passengers of John Worboys about that. A black taxi driver in London – thus a certified possessor of “the knowledge” – in 2009 Worboys was sent to prison for sexually assaulting at least 12 women, usually after drugging them in his cab. He is said to have been one of the most prolific sexual assaulters in UK history. Over 100 women stepped forward and accused him. Police believe his victim count could have exceeded 500.

Closer to home there is Sherman Jackson II, owner and operator of Sherman’s Safe Ride in Butler County, OH, who was charged with sexually assaulting two Miami University students. (Jackson denied the accusation.)

In Washington, DC, Yared Geremew Mekonnen, a taxi driver, was arrested for raping a passenger who, incidentally, had fallen asleep in the backseat of Mekonnen’s cab. When she awoke, she said he was raping her. Mekonnen too denied the allegation.

In Chicago, a taxi driver was arrested for raping drunk Loyola students, according to claims by the prosecutor.

The list could go on. Travis Bickle isn’t the only criminal taxi driver – there are plenty of deviants in real life.

I also could quickly assemble a collection of cases involving Uber and Lyft drivers. Absolutely.

My point is that the National Limousine Association is just plain ignorant if it believes it can make a case that passengers feel less safe in an Uber than a licensed taxi and that they should feel less safe.

In many cases, by the way, ride share drivers are former taxi drivers who say they make more money with the ride share outfits. At least that’s what I have heard from a number of drivers.

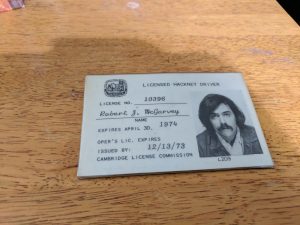

Understand: I personally drove a taxi, off and on, in Boston and Cambridge, Mass. I had hackney licenses issued by both towns. As I recall, the vetting – conducted by the city issuing the license – consisted of taking my fingerprints and running them through an FBI database.

In Phoenix, where I now live, getting a taxi license apparently involves providing a criminal background check.

I am not anti taxi driver.

But I am also not anti Uber driver.

I am against inflammatory ads that hope to stoke groundless fears however.

Look, background checks aren’t that hard. Recently, I offered myself as a volunteer in the Catholic Church in Phoenix. I learned that volunteering requires watching a “Safe Environment” video and filling out a fairly extensive personal history as well as providing three or four personal references and agreeing to a criminal background check.

That may seem a lot but given the Church’s recent history it quite clearly is necessary.

If I can do that much to serve as a volunteer, surely ride-share drivers can do similar.

At Uber they do in fact – which makes the National Limousine Association argument that much more baffling.

Lyft does too.

Also, with Uber and Lyft your ride is logged by the computers. There’s a record of the route and time. That’s more than usually documents a taxi ride.

I am not saying that therefore your safety is guaranteed in an Uber ride – or a medallioned yellow cab. Use your wits. If you feel unsafe, get out. Don’t doubt your instincts.

But very, very probably all will be well, no matter which transportation mode you choose.

Oh, one last slap at the National Limousine Association. A few years ago I was a passenger in a licensed Journal Square, Jersey City taxi where the driver’s license was prominently displayed. I look at such things, probably because of my personal background.

In this case, the photo caught my eye because it was an entirely different person!

And I’m supposed to feel safer in a taxi?

That ride proceeded without incident by the way.

They almost always do.